Microbial Pathogenesis

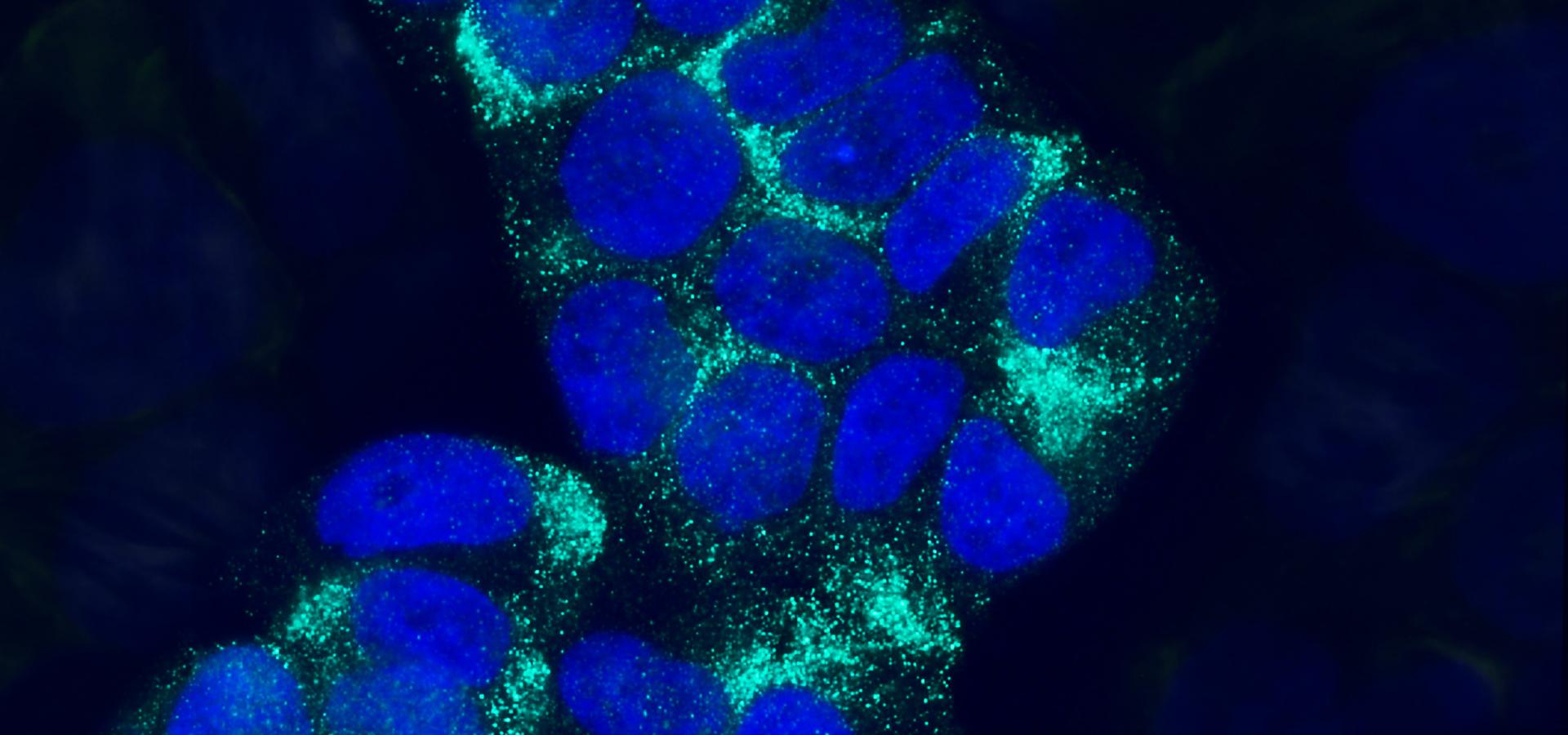

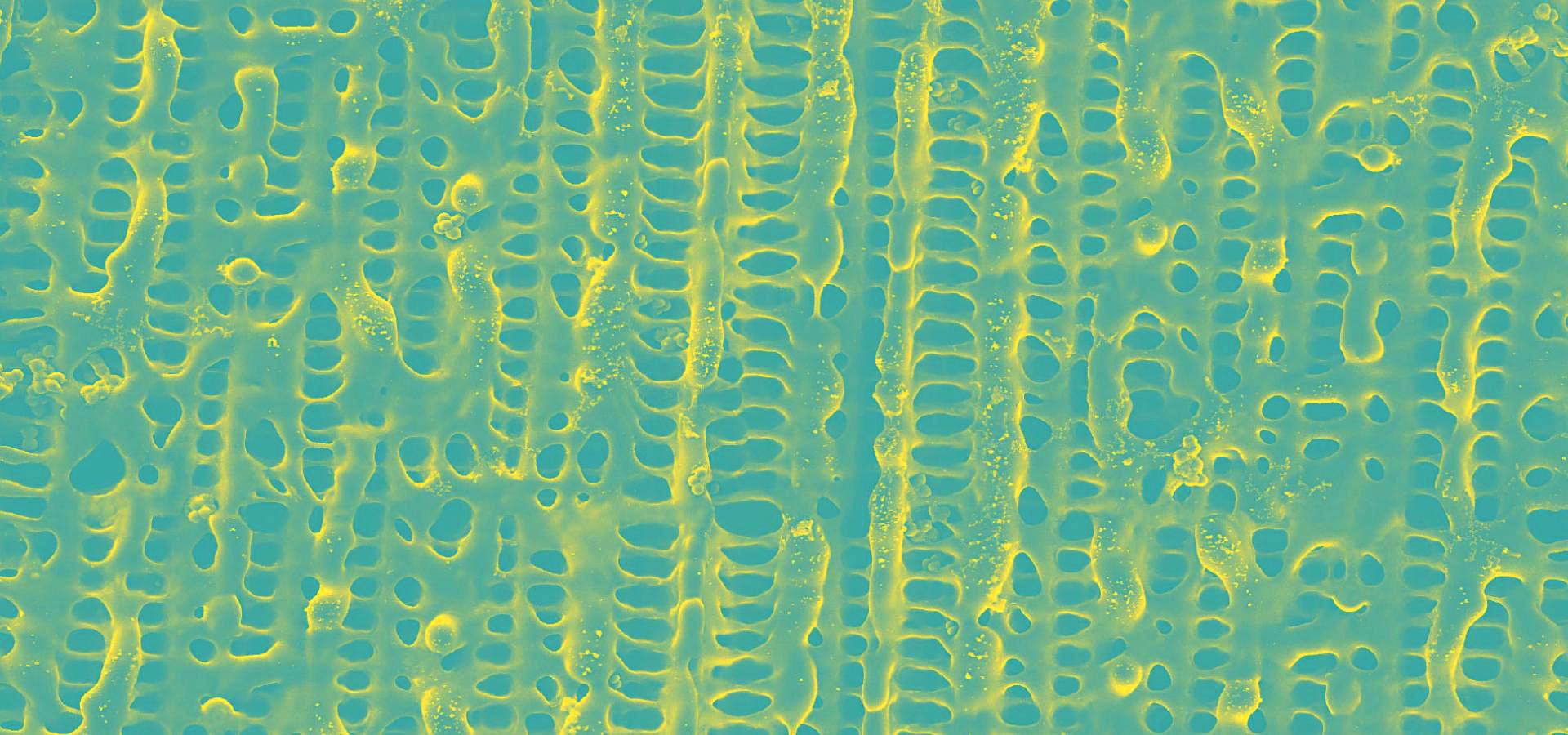

The Microbial Pathogenesis Research Unit seeks to understand at the molecular level how pathogenic bacteria grow when adhering to the surface of medical devices and tissues, leading to infections that are resistant to antibiotics and therefore tend to become chronic. In order to understand this form of bacterial growth, known as biofilm, genetic engineering strategies are used, along with omics approaches, synthetic biology and animal models.

The ultimate goal is to identify the critical elements in biofilm formation in order to prevent biofilm from forming, eliminate already formed biofilm, improve existing treatments and favouring the formation of non-pathogenic bacteria biofilm for therapeutic purposes.

Lines of research:

- Signal transduction mechanisms in bacteria.

- Growth of bacteria with therapeutic purposes and identification of new targets for infection treatment.

- Study of bacterial adhesion to abiotic surfaces (implants) and tissues.

Microbial Pathogenesis Unit of Navarrabiomed-UPNA identifies new gene structure in bacteria that may trigger novel developments in the fields of synthetic biology and bacterial biotechnology

The Microbial Pathogenesis Unit of Navarrabiomed-Public University of Navarra (UPNA) has found a new genetic organisation in bacteria that helps better understand bacterial biology. The study of this genetic architecture was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS).

Research background

In 1961, François Jacob and Jacques Monod discovered that bacteria group the genes that encode the proteins for a certain metabolic pathway in a single transcription unit (which they called ‘operon’). They won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1965 for their discovery.

The bacteria they chose for their study was Escherichia coli, which normally lives in the intestines of healthy people; specifically, they studied the set of genes E. coli bacteria need to transport lactose (milk sugar) and break it down. E. coli only produces the three proteins it needs to digest lactose when the sugar is available. To simplify transcription regulation, the three genes involved are adjacent in the genome and under a single regulation system. Similar transcriptional regulation systems are found in other metabolic pathways in all bacteria.

Research at Navarrabiomed

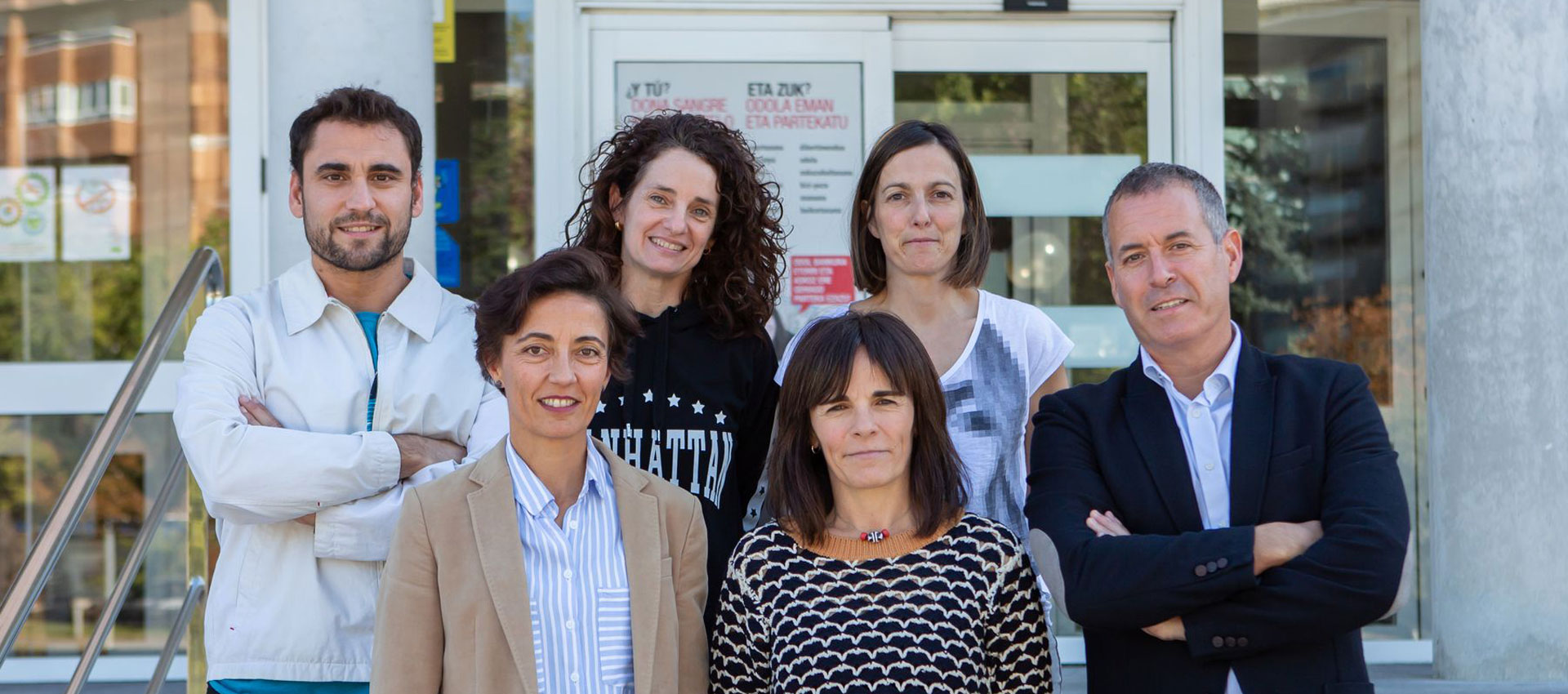

In 2018, the team of researchers at Navarrabiomed coordinated by Iñigo Lasa Uzcudun, Head of the Microbial Pathogenesis Unit and Director of the biomedical research centre, described a new way genes are organised in bacteria. This regulation system has a higher level of regulation in operon structure, which the authors of the study named ‘non-contiguous operon’.

The bacterial model analysed has a group of four genes that are transcribed as a transcription unit despite the existence of a separate gene between the second and third genes that is transcribed in the opposite direction.

This transcriptional architecture results in an antisense transcript that acts as a mutual regulation system for the expression of the genes in the operon and the gene that produces this antisense transcript. Therefore, the concept of non-contiguous operon includes not only the genes transcribed from the same transcription unit but also overlapping genes whose expression is coordinated with that of the genes in the operon.

This finding deepens the understanding of bacterial biology and may trigger novel developments in the fields of synthetic biology and bacterial biotechnology.

The study was carried out as part of the scientific activity done at the Navarra Medical Research Institute (IdiSNA).

Navarrabiomed y la UPNA caracterizan el sistema sensorial de las bacterias para el desarrollo de antibióticos más eficaces

- El estudio, financiado por el Ministerio de Economía, ha sido publicado por la prestigiosa revista Nature Communication.

Un equipo científico del centro de investigación biomédica Navarrabiomed -centro mixto del Gobierno de Navarra y la Universidad Pública de Navarra (UPNA)- ha conseguido caracterizar el sistema sensorial que las bacterias utilizan entre otras cosas para multiplicarse en el cuerpo humano y causar infección.

El avance, que ha sido publicado por la revista científica Nature Communications y cuenta con financiación del Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad, permite comprender mejor cómo las bacterias se adaptan a las diferentes condiciones ambientales y posibilitará el desarrollo de antibióticos más específicos y eficaces.

El estudio ha contado con el liderazgo del doctor Iñigo Lasa, director de Navarrabiomed e investigador responsable del Grupo de Patogénesis Microbiana del centro. Asimismo, han colaborado investigadores del Instituto de Agrobiotecnología (UPNA-CSIC-Gobierno de Navarra), del Instituto de Biomedicina de Valencia (CSIC) y del Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow.

Bacterias superresistentes

Actualmente, la aparición de bacterias farmacorresistentes, que no responden a tratamientos con antibióticos, constituye uno de los problemas sanitarios a escala mundial priorizados por la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS).

Las bacterias detectan, responden y se adaptan a los cambios en su entorno utilizando unos elementos sensoriales denominados sistemas de dos componentes. Este tipo de sistemas sensoriales están presentes en bacterias, hongos y plantas, pero no se encuentran en células animales. En el caso de las bacterias, regulan procesos celulares tan importantes como la virulencia o su propio crecimiento, lo que los convierte en dianas para el diseño de nuevas terapias antimicrobianas.

El objetivo del trabajo ha consistido en eliminar todos los sistemas de dos componentes, es decir el sistema sensorial completo, en Staphylococcus aureus, uno de los principales patógenos humanos según la OMS y, posteriormente, en la generación de una colección de bacterias cada una de las cuales contiene un único sistema de dos-componentes. Esta estrategia ha permitido simplificar una compleja red sensorial en cada uno de sus elementos para comprender cuál es la función individual de cada uno de los sistemas y la relación existente entre ellos.

Aplicación clínica de la investigación

En relación a la aplicación clínica, Iñigo Lasa apunta al desarrollo de nuevos antibióticos más específicos. “El hecho de que los sistemas de dos componentes estén presentes en todas las bacterias patógenas y no en las células de nuestro organismo nos puede permitir desarrollar fármacos que bloqueen estos sistemas, evitando así el desarrollo de la bacteria durante la infección, sin causar ningún efecto secundario sobre nuestras células”.

En este sentido, las bacterias generadas en este estudio han sido patentadas y actualmente el equipo analiza diversos compuestos marinos que puedan incorporarse en el tratamiento y control de infecciones en la práctica clínica.

La investigación forma parte de la actividad científica del Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Navarra (IdiSNA), agrupación público-privada para el fomento de la investigación biomédica en la Comunidad Foral y de la que son miembros Navarrabiomed y la UPNA.

- Información adicional sobre el paper: Behind the paper - Nature Microbiology: "Life without sensing. Can Staphylococcus aureus live without two-component sensorial system?"

Navarrabiomed - Centro de investigación biomédica

Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra, edificio de investigación.

Calle Irunlarrea, 3. 31008 Pamplona, Navarra, España.